Latency Showdown: AWS Lambda vs Azure Cloud Functions vs GCP Cloud Functions

Disclaimer: These results are representative of my specific simulation setup. Simulations with different parameters may yield different results. For example: higher volume, larger function size, different language, different region etc…

Intro

If you’re thinking of using serverless functions, it’s crucial to pick a cloud provider that gives great results without fail. This article compares AWS Lambda, Azure Cloud Functions, and GCP Cloud Functions to see which is the fastest and easiest to use. When you finish reading, you’ll know which one is perfect for your business. Let’s dive into this detailed comparison of the three best serverless function providers!

Results TL;DR

Overall winner: AWS Lambda

| Category | Winner |

|---|---|

| Function latency (lower is better) | AWS |

| Client latency (lower is better) | GCP |

| Ease of setup | AWS |

| Time between cold starts (higher is better) | AWS |

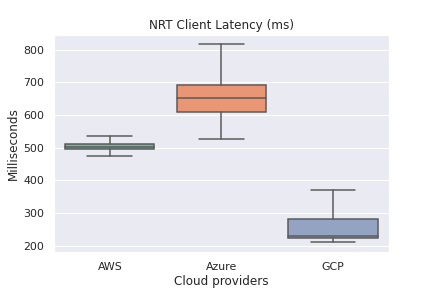

Overall, AWS was the easiest to set up and was the most stable in terms of function latency across all regions. GCP was the fastest in terms of client-side latency and I’m still not completely sure why this is the case. Given that the data centers for each cloud provider are probably close to each other, my best guess would be that GCP’s server-side performance is simply faster.

What I’m looking for

If I needed to deploy to production for a fast and low volume function, I would most likely choose GCP since I would save an extra 100 - 300 milliseconds. However, if the function time was several seconds, I believe that AWS would become more attractive as the performant function time would start offsetting the client-side latency.

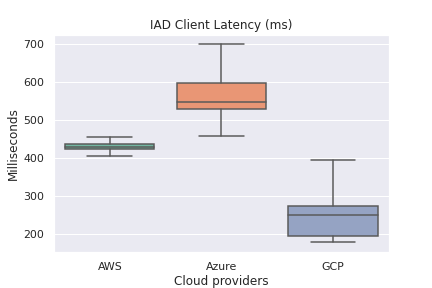

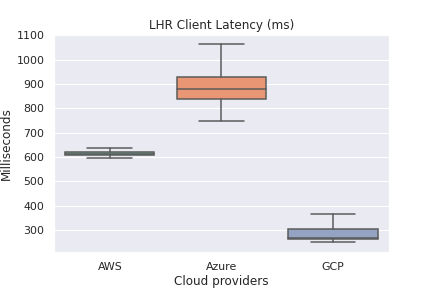

Azure’s client-side latency variance of the box (p75 - p25) was quite high and appeared to be right-skewed. This combined with the numerous paper cuts in the integration, I would not use Azure in a production use-case at the moment.

Caveat: I’m not sure if I should weigh the client-side latency findings too heavily since client-side latency can be impacted by a number of external factors: physical location, server-side latency, network latency, DNS, etc..

Interesting findings

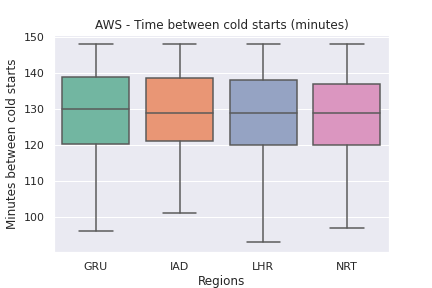

- Even though my call pattern was low-volume (once per minute), AWS Lambda would cold start roughly once every ~130 minutes plus or minus 20 minutes. Reference

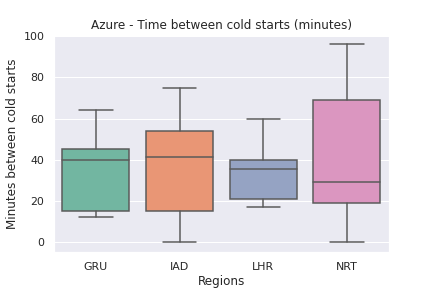

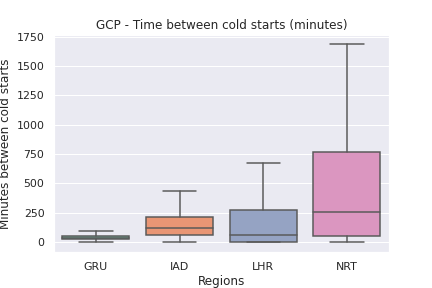

- AWS has the longest median time between cold starts at around 120 minutes. Azure cold starts every ~40 minutes and GCP seems to vary on the cold starts depending on the region. Reference

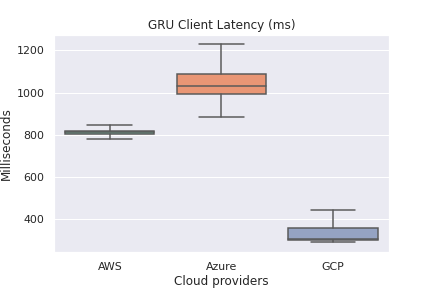

- From a client-side latency perspective, GCP Cloud Functions were the fastest across all regions by 100’s of milliseconds in some cases. Reference There are many explanations for this:

- Server side latency - the time between when the cloud provider receives the invoke request to when the function is invoked

- Network latency - The network hops from the caller to the cloud providers are likely different and could impact latency

- Local setup - In my simulation, I called various cloud providers from a t2.micro EC2 instance in us-west-2. The results could have varied if I used a different network setup or even a different cloud provider.

- All 3 cloud providers are relatively stable when comparing overall client latencies Reference

- For overall function and client latencies, Azure kept up with AWS and GCP Reference

Background

Cloud providers typically provide serverless functions where users provide the business logic and the cloud provider will manage the compute resources, i.e. the functions. In this doc, I will be reviewing the following services:

- AWS - AWS Lambda

- Azure - Cloud Functions

- GCP - Cloud Functions

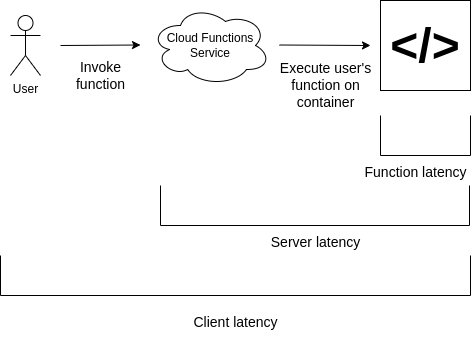

When a serverless function is called, or invoked, the cloud provider will run the user’s code on a container or instance. In this scenario, the total client-side latency is the following:

- User’s code makes request to cloud provider

- Cloud provider calls user’s function

- Run user’s function

- Get the output and return to user

If there is no container available, one will be provisioned. This action introduces additional overhead and is often referred to as a “cold-start”:

- User’s code makes request to cloud provider

- Provision new container (<— cold start)

- Cloud provider calls user’s function

- Run user’s function

- Get the output and return to user

|

|---|

| Fig. 1 - Latency definitions |

Why do this?

In general, there is not a lot of visibility into how much time is spent inside the cloud provider outside of the user’s function. To be specific, these are the open questions that I am hoping to answer:

- How frequently do users see cold starts?

- What is the function latency variance?

- What is the client latency variance?

Out of scope

User isolation

By the nature of distributed systems, a spike in latency or errors for one user does not necessarily indicate a service-wide outage. As such, this analysis is not representative of overall service health. It can only be used to identify the availability of the system for that particular user and their functions.

Hosting

If the canary runs on the same infrastructure as some of the Cloud Functions, that may bias some of the results. For example, the canary running on an AWS EC2 instance calling Lambda may produce different results if the canary was running on a separate hosting provider.

Simulation setup

I have a t2.micro EC2 instance launched in us-west-2 (Oregon). Once per minute, I make requests to function services in each of the 4 regions in AWS, Azure, and GCP. I have chosen specific regions that are in close proximity to each other so that we can get as close to an apples to apples comparison as possible.

| Airport code | AWS | Azure | GCP |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRU | sa-east-1 (São Paulo) | Brazil South (São Paulo State) | southamerica-east1 (São Paulo) |

| IAD | us-east-1 (N. Virginia) | East US (Virginia) | us-east4 (north virginia) |

| LHR | eu-west-2 (London) | UK South (London) | europe-west2 (london) |

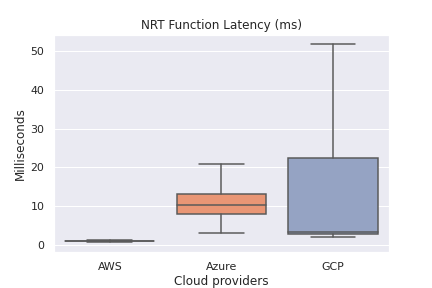

| NRT | ap-northeast-1 (Tokyo) | Japan East (Tokyo) | asia-northeast1 (Tokyo) |

All functions are configured with the following:

- 128MB memory

- Python 3.8 runtime

- x86-based architecture

I am opting to not use additional provider-specific configurations that may help improve performance and reduce cold starts. For this simulation, I am interested in seeing how each service performs out of the box.

Results

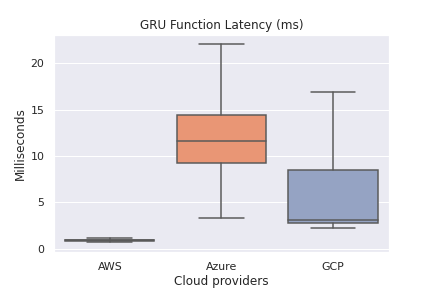

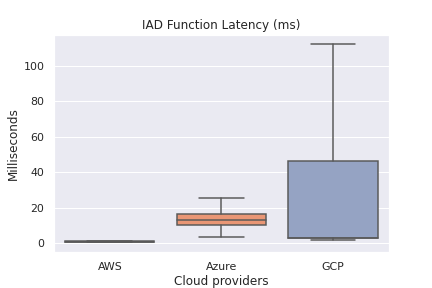

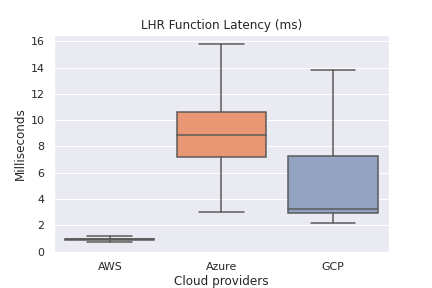

Function Latency (excluding outliers via showfliers = False in seaborn)

Overall Function Latency by Region

Winner: AWS

Client-side latency (excluding outliers via showfliers = False in seaborn)

Overall Client-side Latency

Winner: GCP

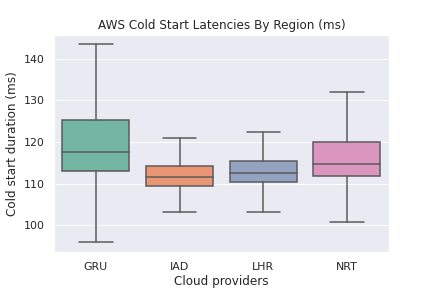

AWS Cold Start Latencies by Region

Time between cold starts

Azure and GCP cold starts

Although I would have preferred to measure the impact of cold starts on Azure and GCP, accurately measuring them at the invoke level is currently not possible.

Azure has the concept of a “HostInstanceId”, which represents the instance on which your invoke ran. However, even if we interpret a new “HostInstanceId” as a cold start, it does not guarantee that Azure is not creating extra instances on the backend for redundancy.

Paper cuts

AWS

Little to no issues here. Integration was very quick. I copy-pasted an example from the boto3 documentation and it worked on the first try. I didn’t have to scan Cloudwatch Logs since the response from Lambda gives you the function duration and the init duration, if there was a cold start.

GCP

Getting the Python Cloud Functions client to work with auth was a bit tedious. The documentation will eventually lead you to this giant web page with all the method definitions that was a bit difficult to go through. The process to make authenticated calls was also unclear and the documentation was difficult to find.

Azure

Azure was the most painful integration. There were several fields I needed to set in order to get the functions working. After I created function keys, they would automatically get deleted after some amount of time. After Googling, I found that I needed to update the lifecycle policy in the storage account. There were cases where Azure would just be missing logs from my invocations so I was unable to get some performance numbers for some of the invocations.